What Happened To The GULF

Two Years After The World's Greatest Oil-Slick

Co-edited by Prof. Abdulaziz Abuzinda and Friedhelm Krupp

Pictures by M. McKinnon & Mike Hill

CLICK ON MAP TO FOR DETAIL (68k JPEG)

The Gulf War oil-slick was not only the largest such instance of human-induced oil pollution ever, it was also one of the biggest news stories of a year in which newsmen worldwide were having field-day after field-day. As so often happens with such high profile news-stories however, there comes a time when editors decide either they, or their public, have had enough. The cessation of reporting on the oil-slick and its consequences was almost as sudden as the events which led to its creation. Whilst news reporters disappeared from the Gulf just as precipitously as they had arrived, the oil itself was rather more persistent. Meanwhile a public who had avidly followed the events of the war itself, and its terrible consequences for both people and wildlife, were suddenly left in the dark. What had happened to all that oil? Was it some sort of propaganda story? Was there really as much as some reports had indicated, or was it a mere drop in the ocean as others had suggested? And what of those poor birds - the bedraggled oil-soaked cormorants who waddled along the black-tarred shores, chased on television screens by protectively clothed wildlife workers? In short, how was it that such a world-shattering story could become a virtual non-event?

The Gulf War oil-slick was not only the largest such instance of human-induced oil pollution ever, it was also one of the biggest news stories of a year in which newsmen worldwide were having field-day after field-day. As so often happens with such high profile news-stories however, there comes a time when editors decide either they, or their public, have had enough. The cessation of reporting on the oil-slick and its consequences was almost as sudden as the events which led to its creation. Whilst news reporters disappeared from the Gulf just as precipitously as they had arrived, the oil itself was rather more persistent. Meanwhile a public who had avidly followed the events of the war itself, and its terrible consequences for both people and wildlife, were suddenly left in the dark. What had happened to all that oil? Was it some sort of propaganda story? Was there really as much as some reports had indicated, or was it a mere drop in the ocean as others had suggested? And what of those poor birds - the bedraggled oil-soaked cormorants who waddled along the black-tarred shores, chased on television screens by protectively clothed wildlife workers? In short, how was it that such a world-shattering story could become a virtual non-event?

Many of those who were in some way or other engaged with these dramatic events have been confronted by confused members of the public, in various parts of the world, who have raised such queries. Some, if not all, of the answers are to be found in a fascinating report published earlier this year in the journal of the Senckenberg Research Institute of Frankfurt a.M. with the joint support of the National Commission for Wildlife Conservation & Development (NCWCD), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and the Commission of the European Communities in Brussels. The scientific report, entitled, The Status of Coastal and Marine Habitats Two Years after the Gulf War Oil Spill is jointly edited by Professor Abdulaziz Abuzinada and Dr Friedhelm Krupp(see book-review)

This special feature for Arabian Wildlife magazine takes a new look at the situation through the eyes and words of the report's authors.

Question:

So was there really as much oil as the more dramatic accounts claimed?

Question:

So was there really as much oil as the more dramatic accounts claimed?

Answer: It was the "largest oil-spill in human history" and: "Nobody will ever be able to determine the exact amount of spilled oil. Estimates range from 2 to 11 million barrels but 6 to 8 million barrels (c.1 million tons) seems most likely".

Question: Where did all the oil go to?

Answer: The vast majority of it was washed ashore. Over 700 kilometres of coastline from southern Kuwait to just north of Jubail were covered by a continuous band of oil. And, "Contrary to earlier predictions there is no evidence of any large-scale sinking of oil..."

Question: What happened to it?

Answer: Much of it is still there, soaked

into the sand and inundating the inter-tidal. The fact that fresh white

sand now covers the sticky goo of oil congealed sediments that created

such a strong impression among visitors who came to see the slick's sickly

bequest, does not mean that the oil has disappeared into thin air. It is

still very much present as anyone who attempts to walk on or dig into these

polluted shores will discover. That is not however the whole story for

where there were particular habitats or species at risk sterling efforts

were made to remove the oil to places where it could do no harm. Thus,

for example, on Qurma island, immediately after the spill, International

Maritime Organisation (IMO) contractors flushed free-flowing oil from heavily

impacted mangrove areas, saving "numerous mangroves".

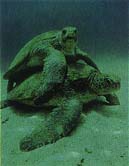

An even more dramatic operation took place on Karan island, famed nesting site for hundreds of turtles and thousands of terns, where "14,000 cubic metres of oiled sediment were removed from the shoreline and replaced by clean sand from the interior of the island", thus allowing "turtles a pollution free access to the beaches". Incidentally, an additional result of this most successful operation was that the accumulated debris of several years flotsam and jetsam were also removed giving the fortunate turtles not just a "pollution free access" but a clear run up the beaches. The oil recovery operations were not only aimed directly at wildlife protection however, but also at the primary aim of containing the slick and reducing its consequences for both man and wildlife. As part of this effort the report reminds us that: "By the end of June 1991 the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia had recovered a record amount of over one million barrels of oil and managed to protect the coastal infrastructures successfully".

Question: Wasn't this all part of an international

effort?

Answer: Very much so. It was in fact a triumph of national and international cooperation. As the report puts it: "Saudi Arabia, with the help of many countries and international organisations, managed to contain this oil spill". The main organisations involved were the Ministry of Defence and Aviation in Saudi Arabia, through its agencies of the NCWCD and MEPA (Meteorological & Environmental Protection Agency); the Royal Commission for Jubail and Yanbu (RCYJ); Saudi ARAMCO, SABIC and the IMO, together with a number of private contractors. Organisations such as the UK based Royal Society for Protection of Cruelty to Animals (the RSPCA) played a valuable role in providing expertise on how to deal with oiled sea-birds.

Question:

Well, what did happen in the end? Was the damage as great as everyone feared?

Question:

Well, what did happen in the end? Was the damage as great as everyone feared?

Answer: The report by Professor Abuzinada

and Dr Krupp is an interim one that takes us up to a period two years after

the Gulf War oil spill. It is not the final story and there will be further

scientific reports of the special team's findings, but answers are beginning

to emerge. The good news is that underwater marine-life is in much better

shape than even the most optimistic of pundits could have predicted. Thus

the report tells us that; "....the damage to sublittoral benthic habitats

was very limited"; and "Macroalgal beds, seagrass beds and coral-reefs

escaped oil contamination..."; and "Two years after the war,

it is obvious that there are no long- term effects of the oil spill on

sublittoral ecosystems such as macroalgal beds, seagrass beds and coral-reefs.

Fish populations, turtles and marine mammals are in a healthy condition".

In support of the above comment on marine mammal, readers of Arabian Wildlife

magazine (Vol.1 No.2) will have seen the report on the Gulf's flourishing

post-war dugong population.

This is not however the complete answer to the question for just as life below tide-level escaped almost "scotfree" (this is the author's description, not that of the scientific editors of this erudite report!), so life in the intertidal, along over 700 kilometres of coastline was massively affected. Thus, we hear that, for example, "Large areas of salt-marshes and mangroves along with their associated fauna were killed. Among vertebrates, marine birds suffered most from the spill and oil covered cormorants struggling to escape from the slick will remain a symbol of this act of ecological terror".

Question: So what has been the recovery

rate in the heavily impacted inter-tidal zone?

Answer: Whereas the situation regarding recovery in the sub- littoral is quite clear, "In the intertidal area the picture is more complex". As one might expect, lower down the shores, where less oil settled in the first place and where the effects of twice daily flushing by tides are more pronounced, there has been much better recovery than near the heavily polluted strand line. Indeed, "The lower eulittoral and sublittoral fringe have largely recovered". On the other hand, "The upper intertidal and the supralittoral fringe are still covered by an almost continuous band of oil and tar". The biological consequences are clear. "Population densities on the impacted shores remain much lower than on unaffected control sites, but in general there is a trend towards recovery with species diversity and population densities increasing".

Question: This does sound better than any

of us expected. Can we be sure that these results are correct?

Answer: Yes we can. A massive amount of research has been undertaken by a multidisciplinary team of about 40 scientists drawn from six countries of the European Union together with about 30 Saudi Arabian and Kuwaiti scientists. Their detailed and comprehensive studies, across a broad range of specialities, all draw the same basic conclusions. As the report itself states: "The EC/NCWCD Wildlife Sanctuary Project has carried out research, survey and monitoring programmes in the area continuously for over two years and is thus able to provide authoritative information on the effects of the oil-spill, on habitats, plant and animal communities and the progress of recovery".

Question: OK, that's fine, but where do

we go from here?

Answer: As the report explains, "Before the crisis, our knowledge of the Arabian Gulf environment was very limited, but after the war more studies have been conducted than in the entire period before 1991. The western Arabian Gulf will soon be one of the better known subtropical seas". This new found knowledge is being put to good use in helping to ensure that the Gulf's marine and coastal life is protected for the future. "The overall aim of the Project is the restoration and maintenance of the area's biological diversity and productivity".

Question: Do you think that is a feasible

objective?

Answer: It is certainly a worthy one. Whether or not it can be achieved will depend very much upon measures which are taken to preserve the Gulf's marine environment as a whole. The report alludes to potential problem areas including industrial developments, on-going pollution and "possible overfishing". The longer term view seems to be that, whilst the patient has escaped on this occasion from what many feared would be terminal illness brought on by a massive overdose of hydrocarbons, the clinical prognosis is that chronic illness will only be prevented by a more controlled regime involving better health-care combined with plenty of "clean-seawater".

Last Question: How did the Gulf's dolphins

escape being decimated by all that oil.

Answer: It seems that they had the common-sense

to get out of the way of it. Let's hope that their skills in this regard

will not be put to the test again!

CLICK ON IMAGE FOR DETAIL (54k JPEG)

![]()

The Status of Coastal and Marine Habitats Two Years after the Gulf War Oil Spill. Abdulaziz H. Abuzinada & Friedhelm Krupp (Editors). Courier Forsch.-Inst. Senckenberg, 166. 1994.

Contents | News | Book Reviews | Back Issues| Forum |

Subjects |

Search | Current Issue | Subscribe

Arabian Wildlife. Volume 2, Number 1